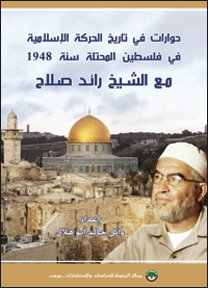

Al-Zaytouna Centre has published a new book, “Dialogues with Sheikh Raed Salah About the History of the Islamic Movement in Occupied Palestine 1948,” prepared by Wa’el Abu Helal.

The first chapter of the 155-page book is offered for free download.

| >> Free Download: Chapter 1: The Historical Testimony of Sheikh Raed Salah |

Publication Information Arabic – Title: Hiwarat fi Tarikh al-Harakah al-Islamiyyah fi Filastin al-Muhtallah Sanat 1948 ma‘ al-Shaykh Ra’ed Salah (Dialogues with Sheikh Raed Salah About the History of the Islamic Movement in Occupied Palestine 1948) – Prepared by: Wa’el Abu Helal |

|

Book Review: Dialogues with Sheikh Raed Salah About the History of the Islamic Movement in Occupied Palestine 1948

By: Yassir Ali.

The Islamic Movement in Palestine has a special characteristic, which is based on the fact that the Zionist project seeks to isolate Palestinian areas from the Arab and Muslim environment. The occupation sought to make Palestinians ignorant there, and tried to tame them by forcing them to stand for the Israeli anthem. They stayed under military rule about twenty years after the Nakbah (Catastrophe) in 1948, until the Naksah (Setback) in 1967, when the 1948 territories were opened to West Bank (WB) and Gaza Strip (GS).

After that, Palestinians from WB and GS, who practiced Da‘wah (Calling people towards Islam’s instructions) went to the 1948 territories and found a fertile environment, where the seeds of Sahwah (Islamic Awakening) could grow. Slowly, the Da‘wah began to spread, and Sheik Raed Salah emphasized in the folds of these dialogues that the care of Allah was present, for he was in the right place (Umm al-Fahm) and the appropriate time (the time of formation), and events pushed him towards the forefront and symbolism (p. 61).

Often, in the history of the Islamic movements, there are two milestones; the establishment and rectification. For after the spread of these movements, they face mandatory questions in their public and political work that were not faced in the mosques … such as the occupation and participation in its institutions and dealing with it. Some called it Qutbi stations (relative to Sayyid Qutb). The Islamic movement in the 1948 occupied territories faced problems different from those faced by WB and GS people. Palestinians there, carry Israeli identity cards, learn in Israeli schools, and register their children and their families in official Israeli registries. There were even attempts to make their conscription compulsory.

Consequently, and after the rise of the Islamic awakening in occupied Palestine in 1948, the movement there, began to face existential questions; such as the recognition of Israel, participation in municipal elections and then parliamentary ones, normalization and media, the ceiling of the struggle and its methods, and the red lines… In addition to questions like: Are they required to have their positions identical to those of WB and GS, and to those of the Arab countries? Defining their relationship with the global Islamic movement, and taking into account their local conditions.

In the history of every Islamic movement, there comes a time for a methodological, educational and organizational change. It would either correct its path, or it would end. These shifts are not free from external influences imposed by the political environment. The movement’s internal currents, are negatively or positively affected by them, and consequently would try to change.

This Book

In this book, the dialogues discuss these two milestones: the establishment and rectification (or the so-called schism). It is based on Sheik Raed Salah memoirs, whose questions were put by Wa’el Abu Helal. The author was interested in two main milestones that he wanted to explore, seeking information from original sources. Some of these dialogues were recorded, and the rest were written.

Abu Helal supported these memoirs with two testimonies; that of the Vice-President of the Islamic Movement Sheikh Kamal Khatib, and the second was by Sheikh Raed Salah companion, Sheikh Hashim ‘Abdul Rahman. The importance of the two testimonies is that their methodology is different from that of Sheikh Raed Salah. Khatib’s testimony is more documented and focused more on the organizational aspects. Sheikh ‘Abdul Rahman’s testimony is a detailed narrative that was not devoid of subtleties.

The three began talking about the awakening and its formation, and how a book by Mustafa Mahmud provided them with the needed thoughts to face the then dominant Communist thought. How a righteous principal encouraged his students to learn Shar‘iah and start the journey of Da‘wah.

Frame and Form

Anyone who searches for the personal aspects of Sheikh Salah’s life will be disappointed. The memoirs focus on his Da‘wah only, putting his personal life aside, thus many of his experiences are not mentioned. However, some of these are found in Sheikh ‘Abdul Rahman’s testimony.

The book is about the Islamic movement in the 1948 Palestinian occupied territories. Sheikh Salah’s memoirs begin from 1973 (the beginning of the awakening, with the “Repentants” group, who were not aware enough of the peaceful methods of Da‘wah). The memoirs stop at the year 2003, without any reason except that the questions of the writer stopped there, as this was the date of the beginning of the stability of the Islamic movement, after the struggle for establishment and the schism.

Although the book’s methodology was based on events rather than years, it did not mention the tunnel uprising of 1996, which was instigated by photos of Sheikh Raed Salah in one of the tunnels under the al-Aqsa Mosque. And for a person who is known be the “Sheikh of al-Aqsa,” the memoirs did not cover as much about the mosque. This is due to the author’s focus on specific aspects of the Islamic movement in the 1948 Palestinian occupied territories, its establishment, course, structure, education, and the role of women in it.

In his testimony, the reader will admire the objectivity and impartiality of a popular activist cleric, who spoke about the history of his work and achievements. This is rare among leaders of the masses.

Content

The memoirs start with the beginnings; the attempts of the occupation to make people ignorant and deform their religion, scarcity of religious books, and the “confrontation of communism without weapons.” The first books were those of Dr. Mustafa Mahmud, “The Quran: An Attempt for a Modern Understanding” and “Dialogue with My Atheist Friend,” in addition to the “Interpretation of the Jalalain.” The sheikhs and jurists left the people, and Islamic history in Israeli curriculum focused on the Battle of Siffin, Battle of the Camel, and the Barmakid Disaster, until WB teachers came to the schools of the 1948 Palestinian occupied territories, introducing new perception and vision. The Naksah in 1967 was a turning point, when communication with WB and GS became possible. This opened the way for the Da‘wah to spread within the 1948 territories, leading to the unity of the Islamic Movement in Palestine once again. Previously, GS belonged to Egypt (Islamists there were treated like the Muslim Brothers (MB) movement were treated in Egypt), and WB belonged to Jordan.

Then came the “Repentants” group, who are some youth who were used to go to cafes then they started to go to the mosques. They were sincere and loyal, but had no knowledge or fiqh (jurisprudence). This sudden shift caused some problems.

The “awakening” of Sheikh Raed and his colleagues began through successive events. First the Islamic movement, in the early 1970s in Kafr Qasim, which was led by Sheikh ‘Abdullah Nimr Darwish and his companions had an impact on them. Preachers and merchants from GS and WB visited them, such as the visit of Sheikh Ahmed Yasin in 1977, who gave them books. Here, Sheikh Raed and his friends began reading the MB Movement books (Hasan al-Banna, Sayyid Qutb, Muhammad Qutb, Muhammad al-Ghazali, Yusuf al-Qaradawi, Fathi Yakan, and others). After that they began to think of a movement.

The turning point in the life of Sheikh Raed Salah was when he decided to study Shari‘ah in Hebron, where he studied with his life companion Sheikh Hashim ‘Abdul Rahman and a number of his colleagues. Then, after them Sheikh Kamal Khatib studied there, too. Consequently, their knowledge of Shari‘ah and Da‘wah guided them to public work in Umm al-Fahm. They started from scratch, leading the Taraweeh prayers (The special evening prayers of Ramadan), Eid prayers, and charities. Then, they formed the Zakat Committee to help those in need, built a night medical clinic, and then developed it into a large hospital of four medical departments.

Then, they held the first major festival in al-Qadr night (Ramadan 27th), calling the youth of the village to contribute. They brought its supplies from schools and mosques, where the head of Municipality Mustafa al-Haj Dawud greatly supported them. At the same time, the Islamic Library project began, reading more books and answering misconceptions about Islam and the philosophical Western material dialectic.

All of this was without establishing an organized movement, so—by then—it was necessary to take this step. They met with Sheikh ‘Abdullah Nimr Darwish and the chore was established. However, the issue of the “Jihad family,” run by Sheikh Darwish (A militant formation of 60 young men from the 1948 territories), and their arrest (1980–1983), were the first crisis they suffered. After that, they started establishing the educational curriculum of the Islamic movement, while coordinating with the Islamic Movement in Hebron. In 1983, the term “Islamic Movement” was known, and in 1984, the organization was formed, having administrative regions.

When Sheikh Darwish left prison in 1983, disagreements with him began to escalate, until schism occurred in 1996. For there was a voting in order to participate in Israeli elections and it failed, then a second voting occurred, but the voters were lobbied. Sheikh Salah addressed the relationship between the two sections of the movement, (and so did the testimony of Sheikh al-Khatib). Salah (in pages 49 and 50) explained the differences between the two parties, which are based on five points:

1. Islamic media and al-Sirat magazine, which contained contested ideas.

2. Scope of the Palestinian–Israeli conflict.

3. Knesset elections and Sheikh Darwish’s desire to participate.

4. General Islamic issues, political stances and relations with the others.

5. Many media statements in the Israel media, and the positions that do not represent the movement’s vision, according to Sheikh Salah.

Sheikh Khatib added three points: Personal convictions of Sheikh Darwish that changed in prison; communicating with Israeli officials, and his direct relations with the Fatah movement.

There are two other reasons that we conclude from the interviews: the relation with the international Islamic movement, and the stance towards the Intifadah (1987–1993)… Sheikh Salah and his team believed that they are directly concerned with these two cases, while Sheikh Darwish thought that the movement must preserve its independence, and stay within the local frame.

After 1996, when the situation exacerbated between the two wings of the Islamic movement, regions were divided according to the selection of the administrative councils of those areas .. Then, the institutions were divided and the wing of Sheikh Raed Salah (the northern wing after the division of areas) relinquished the main institutions in favor of the wing Sheikh Abdullah Nimr Darwish (Southern wing).

The book concludes that the disagreement between the two wings is a political and organizational one. It is clear that Sheikh Salah and Sheikh Khatib, at first, agreed to the result of the vote, and wanted to congratulate Sheikh Darwish, had they not, after that, discovered that voters in the second round were lobbied.

After the separation, advocating for the protection of al-Aqsa Mosque began, the northern wing organized the festival “Al-Aqsa in Danger” attended by about eight thousand people, and then the festival developed until it reached an audience of 40-50 thousand. This popularity was preceded by the success of the Islamic movement in the elections of Umm al-Fahm, where Sheikh Raed became the head of this municipality in 1989. Then, he cooperated with the Higher Follow-up Committee (of the 1948 Palestinians) and represented Umm al-Fahm in local councils. He got open to the outside world when he headed a delegation and participated in several conferences in the United States and others. Moving to the international arena has made Salah in touch with the Islamic movement all over the world, standing in solidarity with the issues of Muslims abroad, such as Bosnia and Herzegovina and those expelled to Marj al-Zuhur.

Although Sheikh Salah, did not talk about himself, however, that “young man” who went in 1978 to learn the Shari‘ah law in Hebron with less than five Palestinians of 1948, founded the Da‘wah and Islamic Sciences College in Umm al-Fahm in 1990. Hundreds of mosque imams and preachers graduated from that college. Therefore, he educated a new generation, who lives in an area that has been completely made ignorant by the occupation.

Readers will find out that Sheikh Salah was a key driver for the success of the Islamic movement. Concerning the establishment of institutions and projects, Sheikh Hashim ‘Abdul Rahman described him as a man “of silence and thought, creative and determined… At each meeting he came up with new proposals and [thought of establishing] new institutions. He was constantly innovating and following up… he worked and developed… he built the institutions himself, then handed them to those who saw them efficient and capable of carrying the responsibility. Then, he would move to a new location without neglecting the old ones.”

After the split, the movement was focused—as Sheikh Sheikh Khatib said in his testimony—on internal construction, through:

1. Structuring the organizational and administrative offices.

2. Reformulation of the educational curriculum.

3. Building legally licensed institutions, and in more than one area: Da‘wah, charity, media and women.

4. Building relations with other constituents of the Arab community in the 1948 Palestinian occupied territories.

The Book’s Importance

This book is the first response from the northern wing of the Islamic movement to the charges of schism. Sheikh Salah and the northern wing were previously reserved in responding to provocation, media attack and attempts to drag them to Israeli courts. They would choose non-disclosure of the Islamic movement papers rather than “airing dirty laundry.” Since the first article of Sheikh Darwish, “Why Did the Brothers Split Apart?” the northern wing remained silent. They insisted on being silent and would work rather than being busy with responses.

Sheikh Salah hoped that the new leadership of the southern wing would start a new era of convergence and harmony, which started during the course of these interviews in 2011. However, what’s expected is a response from the southern wing to the contents of this book. New wrangles could happen, but we hope brotherhood and advice would prevail, seeking truth, and correcting mistakes with constructive criticism.

The historical testimonies in this book make it one of the primary sources to understand the Islamic movement in Palestine, a major reference for researchers in this regard.

Helal focused on two important aspects of the movement’s history: establishment and construction; and schism and rectification. May be because the author wanted to follow the main track of the Islamic movement history, being very important and relatively unknown. Perhaps other books or studies will deal with other aspects.

Generally speaking, the book successfully tackled an important aspect of Palestine’s contemporary history; the history of the Islamic movement in the 1948 occupied territories. The language is smooth-flowing and clear, and the book is well structured.

Leave A Comment