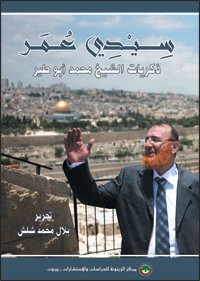

Al-Zaytouna Centre for Studies and Consultations in Beirut issued a new Arabic book entitled Sidi ‘Umar’: The Memoirs of Muhammad Abu Tair.

This is one of the most prominent books on the experience of Palestinian prisoners in Israeli jails published in modern Palestinian history. It chronicles more than forty years of the Palestinian prisoner’s experience.

Sheikh Muhammad Abu Tair is one of the most prominent leaders in Palestine and one of the most prominent symbols of prisoners in Israeli jails, as well as being a former Fatah militant symbol, then a symbol of leadership in Hamas and a member of the Palestinian Legislative Council (PLC). The center offers the Arabic book for free download.

| >> Free Download: Sidi ‘Umar: The Memoirs of Muhammad Abu Tair About Resistance and His 33 Years in Israeli Jails |

Publication Information Arabic – Title: Sidi ‘Umar: Dhikrayat al-Shaykh Muhammad Abu Tair fi al-Muqawamah wa Thalath wa Thalathin ‘Aman min al-I‘tiqal (Sidi ‘Umar: The Memoirs of Muhammad Abu Tair About Resistance and His 33 Years in Israeli Jails) – Edited by: Bilal Mohammad Shalash – Published in: 2017 – Hard Cover: 608 pages – ISBN: 978-9953-500-62-1 – Price: $20  |

|

Book Review: Sidi ‘Umar’: The Memoirs of Muhammad Abu Tair About Resistance and His 33 Years in the Israeli Jails

Reviewed by Dr. Osama al-Ashqar

This is one of the most prominent books on the experience of Palestinian prisoners in Israeli jails published in modern Palestinian history. It chronicles more than forty years of the Palestinian prisoner’s experience, from the viewpoint of Sheikh Muhammad Abu Tair, from his membership of Fatah, then al-Jama‘ah al-Islamiyyah, and then Hamas.

While I was preparing the final draft of this review, news came that the author of this major documentary work was arrested, at dawn on Friday 4/8/2017, for the tenth time in the two months that followed his release from detention. He continues thus his prison experience, which has lasted for more than 35 years… in the past 43 years.

Titled Sidi ‘Umar’: The Memoirs of Muhammad Abu Tair About Resistance and His 33 Years in the Israeli Jails, the 600-page book is comprised of 12 chapters and three appendices, in addition to a timeline detailing crucial milestones in the life of the Jerusalemite Sheikh Muhammad Abu Tair. The book is published by al-Zaytouna Centre for Studies and Consultations in Beirut, which has regularly published biographies of the symbols of national and Islamic action in Palestine.

A Referential Work

The book is edited by Bilal Mohammad Shalash, who began working on the memoirs with Sheikh Abu Tair in mid-2011. Work on the book would be frequently interrupted by the conditions of Abu Tair’s detention. Bilal Shalash’s methodology has been to organize the statements and diaries of Abu Tair into chapters, without intervening in the language of the text or imposing the editor’s vision on it. Bilal Shalash neatly proofed the text and provided bibliographical annotations, expanded on ambiguous terms, and provided biographical information for figures mentioned in the texts. The editor added three appendices that enriched the substance of the book, and an index of figures and places mentioned in the text.

The biography is introduced with a preface by Sheikh Saleh al-‘Arouri, member of Hamas’s politburo and a founder of armed resistance action in the West Bank (WB). ‘Arouri has been a comrade of Sheikh Abu Tair in prison, and has acknowledged his sensitive role in security, military, administrative, political, and religious activities, and his rich pioneering experience.

The biography chronicles the life of the prisoners community in Israeli jails, and their experiences of strikes as well as the shifts in Palestinian revolutionary action. It also chronicles the rise of al-Jama‘ah al-Islamiyyah in the prisons, and on this, the book is a rare testimony. It also chronicles the emergence of Hamas’s armed action in WB in the early 1990s.

The book chronicles not only the Palestinian prisoner movement, but also the Arab prisoner movement in Israeli jails, the prisoners all having in common the Palestinian issue in which they believed and for which they fought for.

In this biography, the personal aspect understandably mixes with the general. It is narrated by its titular figure in a tone full of emotions and experiences, yet general issues slightly overshadow it, perhaps because of the long years of detention and their impact on the life of Abu Tair’s consciousness. To be sure, Abu Tair did not live a normal family life, and has had a longer bond with prison and detention than with family and home.

Literary Language and a Wealth of Information

The language Sheikh Abu Tair has used in his memoirs is eloquent reflecting his linguistic abilities and cultivation. Influenced by one of his secondary school teachers. Abu Tair showed his linguistic skills in some of the poems he had written, including one on the arson attack on al-Aqsa Mosque in pages 43–44, and one eulogizing a Jerusalemite martyr, in page 370. He follows a narrative style marked by many features of oration, using allusions, metaphors, and evocative storytelling devices that emphasize the emotional dimension. This is most evident in his references to Jerusalem and al-Aqsa Mosque, including his witness account of the arson attack on the mosque and his testimony of the Israeli capture of the rest of the city in 1967 in pages 51–52. Abu Tair also adduces a wealth of details in his storytelling, full of figures, places, and stances.

The titles of his chapters are loose and literary, referencing historical stages more than specific issues, yet those stages in some chapters are indeed the main issue. For this reason, the reader may find that the content of some chapters could belong in other chapters carrying titles referencing their main subject.

Sidi ‘Umar and Secret Action

The multitude of figures and secondary characters in the sheikh’s memoirs should not be taken as a sign of indulgence in personal and geographical details. Indeed, because of the small geography of the prison where Abu Tair spent most of his life, where the prison community is small and closely knit, the inmates quickly learn the most intimate details about each other, because of the limitation of other subjects and details.

The editor was keen to provide biographies for as many of the people mentioned as possible, but acknowledged his inability to identify many others, for the lack of documentation provided, bearing in mind that many of the persons mentioned are still alive but received little background information about them, possibly because they have no factional capacity or have deliberately chosen to remain away from the limelight.

The title of the biography carries an important detail about the nature of secret action in the Palestinian revolution, namely, the use of Nomes de Guerre. Sheikh Abu Tair chose for himself the name of a major historical figure at the beginning of his resistance activities with Fatah in the early 1970s, that of the Andalusian conqueror Tarik bin Ziad. With Hamas and its military wing in the early 1990s, he chose the name of the Libyan revolutionary Sheikh Umar al-Mukhtar. Over the years, it became Sidi Umar (Master Umar), out of respect of his seniority, experience, and out of affection for him.

The sheikh’s memoirs also carried important testimonies and advice regarding covert work, especially regarding interrogation, where he said there is a need to train resistance fighters for their arrest and interrogation, where jailers benefit from sharp Palestinian factionalism to recruit agents in prison.

Sheikh Abu Tair criticizes in his memoirs the paranoia among some factions who fear to be infiltrated, which has caused them to make grave mistakes and violations. Abu Tair spoke also about individual mistakes in transferring information inside prisons, and the weakness of security measures by some sensitive operatives, causing major losses for their organizations.

The biography elaborates on the status of Jerusalem in the context of armed resistance, where Jerusalem constituted the “neck bone” for most early military operation.

Testimonies on Figures and Prison Communities

Abu Tair’s memoirs contain old but important details about political and military figures from all factions that continue to wield influence on our present. Such details can shed light on the current positions and political behavior of these factions.

The biography speaks at length about the youths of Al-Qassam Brigades, their enthusiasm, and their steadfastness in prison, and their insistence on returning to the battlefield by any means possible. The sheikh also speaks at length about some martyrs he had known closely, such as Muhyi al-Din al-Sharif, and the brothers Imad and Adel Awadallah. Abu Tair documents the role of Palestinian Authority Security Forces in targeting and smearing them. Although he sometimes omits to identify some key figures in certain stages, he would return in some later chapters to praise their contributions, for example with Sheikh Hassan al-Qiq.

The biography highlights the social aspect of the memoirs, in which he was keen to detail the time, place, and social details of his experience, as well as the family, village, prison, and camp culture, in addition to details about professions and educational institutions…and the impact on figures, their behavior, and their psyches. This includes the effect of regionalism on the psychologies of some Palestinian organizations’ members inside prisons, especially those who do not carry strong ideologies. Then he briefly overviews the effect of regionalism on these once-coherent organizations.

Interestingly, Abu Tair does not skip any details about the reactions of Israeli interrogators to the steadfastness or collapse of prisoners during and after questioning. He painstakingly documented the suffering of the families of the prisoners and detainees as they set out to arrange visits, their role in transferring information and instructions, and their resistance against the tormenting and humiliating treatment of the Israeli forces.

The biography chronicles the emergence of social division between factions based on the position towards the Oslo Accords and the peace process. To be sure, some members of factions of the Palestine Liberation Organization (PLO) were keen to separate themselves from resistance factions, in an attempt to improve the conditions of their detention. Sheikh Abu Tair repeatedly gave a cross-sectional picture of every prison, where prison communities competed among themselves to prove their eligibility to lead, outlining the failures and successes in this regard in various stages.

Interestingly, according to the memoirs, the isolated prisoner community was particularly interested in dreams and visions and their interpretation, which in many cases were the only source of divination, and perhaps even information. In this course, he explains how the position of the visionary and the interpreter raises in this community.

Among the key issues in this biography also, is the experience of Lebanese Shia groups such as Hezbollah and Amal Movement inside Israeli prisons, in terms of their rituals, relations, security precautions, and the stance of factions towards them.

The biography of Sheikh Abu Tair contains many of his quick critical remarks regarding the track record of the Palestinian Islamic Movement, at the level of approach, organizational conduct, and intellectual base, in addition to important historic critiques of the Palestinian and Arab media and political climate linked to the Palestinian situation.

A Qualitative Academic Addition

Sheikh Abu Tair’s memoirs is rich of oral narrative details on events and episodes that have not received their fair share of academic attention. Therefore, they constitute an enrichment of Palestinian historical research, as in for example his narration of the events before the fall of Jerusalem in 1967. The Sheikh’s culture appears stark in summoning history and the Prophet’s way of life, highlighting patterns and parallels with modern day events and the different ways in dealing with them then and now. He is also extremely critical of the conduct of Gamal Abdel Nasser regime in all the milestones of the conflict in Palestine, and the conduct of the Arab Socialist Ba’ath Party in Syria.

The memoirs reflect the early stances of the Islamic Movement in a phase marked by conflict of identity, for example with the positions on Communist, Marxist, and Leninist ideas and movements in Palestine, which Sheikh Abu Tair saw as anti-Islamic and must be neutralized. Abu Tair overviewed his own experience in rebutting their ideas and arguments through cultivation and reading, particularly the works of Muhammad Qutb.

The memoirs narrate the details of the daily lives of the prisoners, concerning their food, drink, clothing, climate, conditions, and emotions, as well as dealings with their jailers and other inmates. Moreover, their movements, interrogation, and experience in resisting this reality psychologically, socially, behaviorally, and tactically, and the waves of intense escalation and preemption against them. Abu Tair described the ideologically diverse prisoner community, which included leftists, revolutionaries, sectarianists, nationalists, atheists, and Islamists. The prisoners, according to the memoirs, fell victim into a psychological siege in addition to the denial of their freedoms. In this regard, Abu Tair overviews the harsh ideological experience with the prison inmates and the extent of psychological pressure on the Islamists in the 1970s coming from their supposed brothers in arms. In addition, he explains how prisons in that decade became a center of anti-religious, leftist, and atheist ideas, sometimes using violence, rumors, the burning of religious books, and verbal provocation and incitement.

He poignantly documented the experiences that Hamas underwent alone without support from other factions in imprisonment, in the period of Hamas’s expanding military action in the late 1990s, to avoid violent retribution by the jailers. Abu Tair also documented the list of demands the prisoners wanted to be met by the occupation using all means available, managing negotiations with the occupation regarding the demands, and the extent of pressure placed by Israeli courts, the stalling, and Israel’s use of the prisoners issue to put pressure on the resistance. This was particularly evident in the issue of the Israeli prisoner Gilad Shalit, when prisoners were denied basic rights like food and drink, and were systematically humiliated, with kitchen utensils and appliances seized, not to mention long periods of shackling and restraining, and sudden inspections.

Abu Tair briefly tackles, in separate unlinked places, organizational activities in prisons, such as election mechanisms, leadership committees, and internal departments. He spoke proudly about how leaders in prisons encouraged breakout attempts carried out by a number of prisoners carrying long and life sentences. He elaborated on the role of those elections in addressing negative phenomena such as regionalism and political divisions, and in altering the mechanisms of confronting the reality of prisons, confronting the measures of the occupation including solitary confinement, inspection, visits, meals, prayer, and phone rights.

al-Jama‘ah al-Islamiyyah in Prisons

The information provided on the rise of al-Jama‘ah al-Islamiyyah in Ramleh Prison, Ashkelon Prison, and Hebron Prison are among the most prominent testimonies included in the memoirs. Abu Tair attributes the emergence of al-Jama‘ah al-Islamiyyah to the nature of the provocations religious prisoners were subjected to by their comrades, and the strong influence of Communist ideas in the ranks of the Palestinian National Movement that encouraged anti-religious sentiment. This was met by religious youths by self-cultivation through the books of Sayyid Qutb and his brother Muhammad, Abbas al-Aqqad, Hassan al-Banna, Yusuf al-Qaradawi, Mohamed Said Ramadan al-Bouti, and Mounir Shafiq. Abu Tair reveals that he and his comrades did not at first want to found an Islamic group like the one created by Jaber ‘Ammar in the Ashkelon Prison, as much as their goal was to encourage religious commitment and education, and create a psychologically stable climate for religious prisoners. However, the anti-religious pressure was

too harsh, prompting them in the end to create an organizational framework that brought them together.

Sheikh Abu Tair narrated the stage that saw the establishment of al-Jama‘ah al-Islamiyyah in the prisons, mentioning its symbols, and how rival Palestinian groups sought to violently nip it in the bud, and how the group managed to counter this. The group then sought to engage with Palestinian criminal prisoners, who were neglected by Palestinian factions, and rehabilitate them. The group also struggled for its members to get their own ward, with a religious library and a place to pray and deliver the Friday sermon, despite rejection by rival factions. Moreover, they strived to impose the call to prayer and have the right to grow beards, which was prohibited at the time as a sign of religious identity.

Abu Tair recounted the details of the emergence of al-Jama‘ah al-Islamiyyah in Ashkelon Prison and its most prominent symbols, and how the two branches of the group united around the same ideas during the regular transfers between prisons.

Abu Tair then tackles the phase that saw many youths from al-Jama‘ah al-Islamiyyah move to the Muslim Brotherhood (MB) school of thought or the Palestinian Islamic Jihad (PIJ) school of thought influenced by Khomeini’s ideas in Iran. Many of the group’s youths were members of the Popular Liberation Forces of the Palestinian Liberation Army, or fighters from outside Palestine.

The biography was keen to highlight the faith dimension of the members of al-Jama‘ah al-Islamiyyah and the Islamic movement in the Israeli prisons, and how it helped to solidify the national awareness and commitment to the Palestinian Issue, as these were made equivalent to religious duty.

The Experience of Hamas

The memoirs document for the first time how negotiations and then a prisoner swap was carried out between the Popular Front for the Liberation of Palestine- General Command (PFLP-GC) and Israel in 1985 from the viewpoint inside the prisons. Sheikh Abu Tair was in charge of sorting and selecting criteria for who was included and addressing the problems and Israeli tactics during the negotiations until the swap took place.

No less importantly, the memoirs document the important role of Palestinian prisoners in negotiations behind the prisoner swap that saw the release of around 1,000 Palestinian prisoners in return for Israeli soldier Gilaad Shalit.

The memoirs contain accurate testimonies obtained from Sheikh Ahmed Yassin inside prison regarding the causes of his paralysis, the assassination of Dr. Isma’il al-Khatib, and the creation of the Islamic University in Gaza despite a decision by Yasir ‘Arafat to prevent it by force.

The memoirs include brief accounts of the launch of Hamas in 1987, the WB role, and the coordination between it and Gaza, and who was in charge of this coordination. Also, the start of Hamas’s military activity in WB and its most prominent symbols, how Hamas overcame internal organizational hesitation by summoning the support of Hamas leaders abroad. Moreover, the memoirs tackles Hamas suffering to consolidate its influence and presence in WB cities and villages, and how it was able to withstand Fatah’s decisions to liquidate it and prevent it from growing and expanding in those areas. Abu Tair then expounds on the Israeli policies meant to counter Hamas, delivering successive blows against the group in the early 1990s, especially in terms of arrests, torture, and banishment.

In his own experience during the election of 2006, which led to a major victory for the Hamas-affiliated Change and Reform bloc, he came second on the list led by Isma‘il Haniyyah,. Abu Tair overviews the policies of their rivals from Fatah in dealing with them, documenting many violations and assaults in this regard, and the reaction of the public to Hamas especially among Palestinian Christians and refugees. He also tackles the position of Hizb ut-Tahrir on the elections, and how it caused some loss of popular momentum with its fatwas that targeted Hamas more than it targeted other factions. Abu Tair also details the measures signed by Mahmud ‘Abbas and the policies of Fatah to deny Hamas the gains resulting from its electoral victory, and how Israel sought to deflate its newfound political presence by taking harsh measures against Hamas lawmakers, most seriously when it revoked Jerusalem residency for Hamas’s Jerusalem MPs.

The memoirs contain a personal statement of political positions by Sheikh Abu Tair, including the position on the Oslo Accords, which he believes to be the most sinister Zionist project implemented by Palestinian hands, for having struck down the Palestinian national project from within, and establishing the Palestinian Authority (PA) agencies to serve the Israel and its security. He also addresses the Palestinian political division, which according to him was a bane of the Palestinian people, resulting from the PA’s commitment to the Israel’s security and interests at the expense of the interests of the Palestinian people. On Hamas’s military takeover of Gaza in 2007, he says this was the only way to counter the brutality of the Palestinian Security Forces and their Zionist project to strike down and liquidate the resistance. Abu Tair strongly defends the resistance project, insisting it is the only way to restore rights and liberate the prisoners.

Not everything in the memoirs directly documents events or positions. Rather, it raises long issues about events that took place outside prison, which Abu Tair learned of from the media or his comrades after his release, or from people he met who are involved in these events. In these cases, the narration is often accompanied by personal opinion regarding those issues.

The Arabic version of “Book Review” article appeared on Al Jazeera.net on 10/8/2017.

Al-Zaytouna Centre for Studies and Consultations, 24/8/2017

Hi Is there an English Translation available of this book?

Unfortunately, there is no English translation available at the moment. The book is currently only in Arabic.