By: Dr. Sa‘id al-Dahshan.[*]

(Exclusively for al-Zaytouna Centre).

Abstract

To compare the Israeli attacks against Palestinian civilians in the Gaza Strip (GS) before and after 2015, data was compiled for the analysis and comparison of Israeli attacks in terms of type, objective and outcome. The study covers ten years divided into two periods of equal length: Five years before 2015 (2010–2014), compared to five years after (2015–2019). To carry out the comparison, three areas have been identified, namely:

1. Casualties

2. Attacks

3. Targets

Based on comparing the compiled statistics, the author concluded that there has been a significant decline in the number of killed over the period in question. From 2,730 in the first period, the fatalities toll decreased to 436 in the second period, while the percentage of women and children of those killed declined from 34.4% down to 21.6%. When comparing the ratio of the dead to the wounded in each period, it was found to be 51 wounded for every 10 killed in the first period, which increased dramatically to 508 wounded for every 10 killed in the second period.

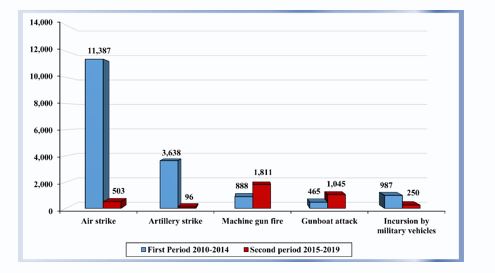

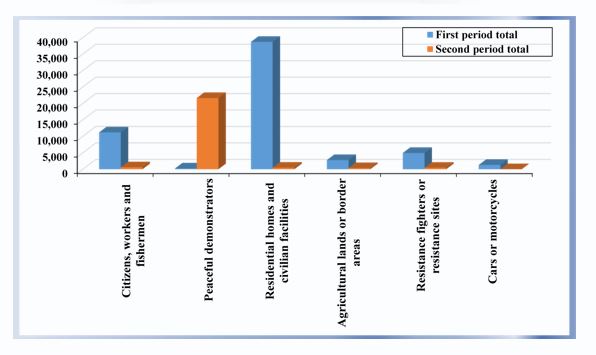

As for the attacks on GS, their number declined between the two periods, from 17,365 to 3,705, accompanied by a qualitatively downward trend in terms of air and artillery strikes, from 15,025 such attacks in the first period to 599 in the second. The proportion of air and artillery strikes to overall types of Israeli attacks also declined from 86.5 % to 16.1%. Moreover, the number of targets hit declined from 59,155 to 23,464. The Israeli army also stopped targeting certain types of targets, such as vehicles, motorbikes and residential homes. Conversely, targeting of peaceful protesters increased. All the above confirms Israel has modified the scale and nature of its attacks on GS following Palestine’s accession to the International Criminal Court (ICC) in 2015, with Israeli attacks declining in number and changing in nature.

| Click here to download: >> Academic Paper: Comparative Study on Israeli Attacks on Gaza Strip Before and After Palestine’s Accession to the International Criminal Court … Dr. Sa‘id al-Dahshan |

Introduction

1. Why 2015?

After the conclusion of the war on GS in the summer of 2014, which had lasted 51 days, popular and political pressure on the Palestinian Authority (PA) to join the Rome Statute establishing the ICC increased, with the aim of prosecuting suspected Israeli war criminals. Indeed in 2015, the Palestinian government officially applied to join the ICC, to take effect on 1/4/2015. The ICC is the first permanent international criminal court. Its jurisdiction covers any person who commits a crime referred to in Article 5 of its statute in accordance with the terms of jurisdiction. There is no immunity for anyone, regardless of their position or nationality. At that time, a wide debate arose among specialists and those concerned about the impact of that accession regarding the nature of Israeli military attacks against Palestinian civilians in GS. Some claimed Israel would do nothing to change its military tactics against civilians, being indifferent to international law or the ICC. Others argued that Israel would alter its tactics quantitatively and qualitatively vis-à-vis Palestinian civilians. Others were more optimistic saying Israel will completely stop targeting civilians and civilian targets, and will only target the Palestinian resistance.

Prompted by this debate, the author has decided to analyze primary sources, including human rights reports, to develop a comparative statistical study on the number of attacks, their quality, the victims and their nature, and the targets affected and their quality, in order to understand the extent of the changes if any in Israeli military conduct towards GS, and the implications for the magnitude and type of attacks on the Strip, between two periods of equal length, the first from 2010 to 2014, and the second from 2015 to 2019.

2. Changes and Causes?

Observing Israel’s conduct in the five years that followed the accession to the ICC, one notes that Israel did not stop targeting GS from time to time; or rather it has altered its military tactics to adapt to the most important variable in the view of the author. This is while taking into account the fact that the five-year period in question (2015–2019) had witnessed several other developments in Palestine, Israel, the region and the world. These developments may have, to one degree or another, contributed in influencing upward or downward the scale and nature of Israeli military attacks on GS. The objective of this study is to determine whether there have been any changes in the nature of the Israeli attacks on the Strip. If there have been changes, the objective is also to determine their extent and quality. As for researching the causes of those changes, if any, and the extent of the contribution of each cause or factor in influencing those changes, this should be the subject of another research that may build on the result of this study. In spite of that, in the conclusion of this study, there will be a brief discussion on the direction of other factors in whether or not they create an environment that pushes for an increase or a decrease in these attacks, which were supposed to be reflected in the size and quality of the Israeli attacks on GS.

Methodology

To this end, the author identified the geographical scope of the study as being GS, the Palestinian area most frequently targeted by the Israeli army. The timeframe was limited to ten years, divided into two periods, the first includes the years 2010–2014, and the second includes the years 2015–2019, which will be termed the two study periods. Three areas were identified for comparison between the two study periods, namely:

1. The number of Palestinian casualties in GS.

2. Israeli attacks on GS.

3. The types of targets that Israeli forces hit in GS. The author also designated a number of subcategories within each area.

A comparison was subsequently made in all fields and categories between the two study periods. The official and documented statistics issued by Palestinian Human Rights Centers have been relied upon, in particular the Al-Mezan Center for Human Rights and the Palestinian Centre for Human Rights. When figures differed between them, Al-Mezan Center’s data was given precedence given the high quality of its work and specialization in GS. This is while noting the high accuracy of these reports, considered objective evidence that can be used to make precise inferences and conclusions, and noting the margin of error of 5% adopted by these centers. Consequently, the methodology of this study is a statistical comparative analysis.

Regarding the methodology of dealing with undetailed data and statistics, as required by some categories and segments in this study, these were dealt with as follows:

In the case of attacks involving machine guns, and when they are not covered by the reports above, these were identified through: the number of fatalities and injuries in border zones, such as among farmers and salvage workers; and the number of dead or injured during peaceful protests near the GS border fence, most likely the result of machine gun fire.

As for identifying the number of dead and injured among resistance fighters out of the total number of casualties in a given year, this was done as follows:

If unmentioned in the reports of Al-Mezan Center, then the data of the Palestinian Centre for Human Rights is consulted. Otherwise, the ratio is calculated as follows: 30% of casualties will be resistance fighters and 70% will be civilians, a ratio inferred from previous annual years and three previous wars in GS.

The targeting of government and municipal buildings was added to the category of civilian homes and structures. This is while noting that this study recognized only civilian structures which were destroyed completely or partially, but excluded homes that suffered minor damages, while stating the references and sources in each case.

This study was divided into three branches:

1. Comparative analysis of casualty figures.

2. Comparative analysis of attacks.

3. Comparative analysis of targets deliberately chosen by the Israeli forces in GS between the two study periods.

First Branch: Comparative Analysis of Casualty Figures in GS in the Two Study Periods

Of course, the data in the institutions’ reports was not categorized in the way the study has sought to do, which required performing calculations in some categories. With regard to the casualties, the author classified them into three categories, namely:

1. Fatalities among women and children.

2. Other fatalities.

3. Wounded.

The “Other fatalities” category was not divided into further categories such as resistance fighters and civilians, due to the lack of accurate data for all the ten years under study. However, the issue of resistance fighters when they were targets, whether wounded or killed (martyrs) was dealt with in the third section concerned with targets, where there is a need here to compare between fatalities and injuries in general. The data for each year is presented in the following table to give a detailed picture. The data for the first five years were grouped together, as well as the data for the last five years in another group to facilitate analysis, comparison and drawing conclusions after that.

Table 1: Palestinian Casualties in the Two Periods

| Year | Women[1] and children[2] killed | Other fatalities [3] | Total fatalities | Total wounded |

| 2010[4] | 5 | 67 | 72 | 209 |

| 2011[5] | 15 | 99 | 114 | 467 |

| 2012[6] | 56 | 196 | 252 | 1,473 |

| 2013[7] | 2 | 10 | 12 | 75 |

| 2014[8] | 862 | 1,418 | 2,280 | 11,724 |

| First period total | 940 | 1,790 | 2,730 | 13,948 |

| 2015[9] | 5 | 23 | 28 | 1,275 |

| 2016[10] | 4 | 5 | 9 | 221 |

| 2017[11] | 3 | 26 | 29 | 902 |

| 2018[12] | 52 | 210 | 262 | 13,946 |

| 2019[13] | 30 | 78 | 108 | 5,821 |

| Second period total | 94 | 342 | 436 | 22,165

|

It is worth noting that the year 2012 witnessed a large Israeli military offensive known as (Battle of Shale Stone/ Pillar of Cloud), which lasted for eight days between 14–21/11/2012, during which 179 were killed. This explains the relative increase in the number of casualties compared to 2011. As for 2013, there was a significant decrease in victims; in the opinion of the researcher this was due to two reasons: First, the regional role of Egyptian diplomacy during the term of President Muhammad Morsi, and second, the Israeli cautious anticipation of the dramatic changes in Egypt and the overthrow of Morsi. Then in 2014, there was a significant increase in casualties, perhaps in an unprecedented escalation since the 1967 occupation. This year witnessed the longest period of battles between Israel and the Palestinian resistance, which lasted for 51 continuous days, during which the Israeli army carried out all forms of aggression using all types of weapons, rockets, missiles, and explosives, which left a large number of casualties, in addition to widespread destruction of infrastructure, housing, and civilian facilities, in all the cities and towns of GS.

It is also possible to observe a significant decrease in the number of casualties in the three years that followed Palestine’s accession to the ICC, i.e., 2015, 2016 and 2017. Then 2018 and 2019 witnessed the Great Return Marches, which led to an increase in the number of casualties. Despite this, the casualty numbers did not match the period prior to the accession to the ICC. Perhaps the reason for the uptick is due to the Israeli army’s decision to suppress the return marches,[14] considering it a real threat to Israel, and therefore it was confronted with excessive and lethal force, which led to a noticeable increase in the number of casualties in 2018 and 2019.

By studying the previous table, and carrying out a comparison between the two study periods, the following results can be obtained:

1. The number of killed[15] decreased dramatically in the second period compared to the first period. The total number of fatalities in the first period was 2,730 people, which decreased to 436 people in the second period, meaning that fatalities in the first period represented more than six times the figure in the second one.

2. There was a qualitative decline in the number of women and children killed. In the first period, they numbered 940 out of 2,730 killed or about 34.4% of the total number of fatalities. In the second period the number dropped to 94 out of 436 killed or about 21.6% of the total number of fatalities.

3. The number of wounded in the first period was 13,948, increasing significantly in the second period to 22,165, with a total of 36,113 wounded in the two periods, meaning that the second period alone represents more than 61% of the total number of wounded, due to the Great Return Marches.

4. The ratio of the wounded to the fatalities in the first period was about five times higher, specifically, every 10 killed corresponded to 51 wounded, while in the second period the ratio increased about 51-fold, meaning that every 10 dead corresponded to 508 wounded.

5. Most of the injuries in the second period occurred during 2018 and 2019, as 13,946 people were injured in 2018, while 5,821 people were injured in 2019, due to the return marches that greatly increased the number of the wounded. Incidentally, the percentage of the wounded in these two years represents more than 89% of those wounded in the entire second period!

Second Branch: Comparative Analysis of Israeli Attacks on GS Before and After Palestine’s Accession to the ICC

The analysis of attacks[16] and weapons used in every attack aims to show the qualitative and quantitative changes in the use of weapons. As is known, attacks using heavy weapons such as air strikes or artillery strikes cause much greater destruction than machine guns or incursions. These attacks were divided into five categories based on the type of weapons used. The data was presented for each year for more detail, then the data for each period of the two study periods was grouped together, as follows:

Table 2: Israeli Attacks on GS in the Two Study Periods

| Type of Israeli attacks | Air strike | Artillery strike | Machine gun fire | Gunboat attack | Incursion by military vehicles | Total |

| 2010[17] | 74 | 22 | 152 | 49 | 81 | 378 |

| 2011[18] | 193 | 44 | 89 | 66 | 43 | 435 |

| 2012[19] | 1,540 | 29 | 43 | 120 | 46 | 1,778 |

| 2013[20] | 20 | 8 | 154 | 147 | 56 | 385 |

| 2014[21] | 9,560 | 3,535 | 450 | 83 | 761 | 14,389 |

| First period total | 11,387 | 3,638 | 888 | 465 | 987 | 17,365 |

| 2015[22] | 27 | 5 | 182 | 126 | 33 | 373 |

| 2016[23] | 56 | 14 | 132 | 141 | 55 | 398 |

| 2017[24] | 53 | 17 | 240 | 213 | 51 | 574 |

| 2018[25] | 150 | 41 | 510 | 218 | 52 | 971 |

| 2019[26] | 217 | 19 | 747 | 347 | 59 | 1,389 |

| Second period total | 503 | 96 | 1,811 | 1,045 | 250 | 3,705 |

By studying the table above and comparing the results between the periods before and after the accession to the ICC, the following can be deduced:

1. There is a marked decrease in the number of Israeli attacks in general, despite the weekly Great Return Marches in 2018 and 2019, which did not impact the result of this study. Indeed, the number of attacks is not the same before and after the accession to the ICC, dropping from 17,365 or 82% of the total for both periods to 3,705 attacks or 18% of the total.

* Comparing the Categories of the Attacks in the Two Periods

2. There is a marked decrease in the number of attacks in three specific categories in the second period: Air strikes, artillery strikes, and incursion by military vehicles; while machine gun and gunboat attacks increased in the second period.

3. There is a marked decrease in Israel’s use of heavy weapons (air strikes and artillery strikes). In the first period, there were 15,025 such attacks, representing 96% of the total for both periods, declining to 599 or 4% in the second period. This has important implications in this study. As is known, targeting civilian areas with bombardment is considered a war crime, and it seems that Israel has started to hedge for the ICC, impacting its military tactics quantitatively and qualitatively.

4. There is also a marked decrease in the use of heavy weapons in attacks, relative to other types of weapons, in the second period. Indeed, the ratio of air and artillery bombardment to the rest of the types of attacks in the first period was about 86.5% of total attacks, meaning that out of every 100 attacks in the first period, there were about 87 attacks using heavy weapons. In the second period, Israel decreased the use of heavy weapons compared to the rest of the types of weapons and attacks, to become only 16.1% of the total attacks, meaning that out of every 100 attacks in the second period, 16 attacks used heavy weapons, which underscores a qualitative decline, in addition to the numerical decline in attacks.

Third Branch: Comparative Analysis of Targets Deliberately Chosen by the Israeli Forces in GS Between the Two Study Periods

With regard to the deliberate targets of the Israeli army forces and its military arms, they are many and varied, but for the sake of clarifying the picture and for the purposes of standardized comparison, the author has divided these targets into six categories:

1. Citizens, workers and fishermen.

2. Peaceful demonstrators.

3. Residential homes and civilian facilities.

4. Agricultural lands or border areas.

5. Resistance fighters or resistance sites.

6. Cars or motorcycles.

The data has been presented in detail for each year and then grouped together for each of the two study periods. The following table provides a detailed presentation of the numbers and types of targets that the Israeli forces attacked during the two study periods (2010–2014) and (2015–2019).

Table 3: Types of Targets Attacked by Israel During the Two Periods

| Target Type | Citizens, workers and fishermen | Peaceful demonstrators | Residential homes and civilian facilities | Agricultural lands or border areas | Resistance fighters or resistance sites | Cars or motorcycles | Total |

| 2010[27] | 144 | 33 | 214 | 189 | 11 | 13 | 604 |

| 2011[28] | 299 | 108 | 115 | 118 | 243 | 24 | 907 |

| 2012[29] | 1,222 | 48 | 2,846 | 206 | 522 | 94 | 4,938 |

| 2013[30] | 99 | 0 | 26 | 60 | 20 | 2 | 207 |

| 2014[31] | 9,411 | 48 | 35,504 | 2,213 | 4,145 | 1,178 | 52,499 |

| First period total | 11,175 | 237 | 38,705 | 2,786 | 4,941 | 1,311 | 59,155 |

| 2015[32] | 74 | 1,222 | 5 | 38 | 40 | 0 | 1,379 |

| 2016[33] | 71 | 184 | 4 | 75 | 7 | 0 | 341 |

| 2017[34] | 94 | 763 | 6 | 61 | 101 | 0 | 1,025 |

| 2018[35] | 165 | 13,913 | 29 | 106 | 169 | 3 | 14,385 |

| 2019[36] | 192 | 5,536 | 425 | 60 | 120 | 1 | 6,334 |

| Second period total | 596 | 21,618 | 469 | 340 | 437 | 4 | 23,464 |

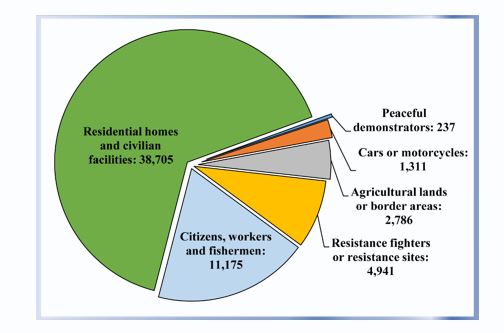

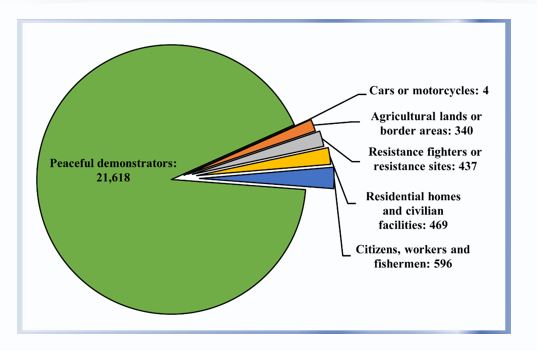

1. The table shows that the targets Israel deliberately bombed in the first period amounted to 59,155, which represents about 71.6% of the total targets in the two periods, while the targets that Israel hit in the second period amounted to 23,464, which represents 28.4% of the total of all targets in the two periods. This gives further evidence of the major change in the Israeli military behavior towards the GS between the two periods.

2. If we exclude the peaceful demonstrators from both periods, given the different context, we will find that the number of targets in the first period was 58,918, while the total of the targets in the second period would be 1,846. This means that the first period witnessed about 97% of the total targets hit in both periods after excluding peaceful demonstrators.

3. After a detailed comparison between the groups in both periods, it becomes evident that there has been a significant decline in all targets across all groups, with the exception of the peaceful demonstrators. It is noteworthy that some groups have been targeted less to large degrees that almost reach zero in the second period, such as cars and motorcycles, and close to that, the category of houses, which represents only 1% of targets in the second period. This indicates a remarkable change in Israeli military behavior, especially since targeting civilian installations and objects is a war crime, according to the Fourth Geneva Convention.

4. On the contrary, targeting peaceful demonstrators has jumped dramatically. In the first period, there were 237 attacks, and in the second period 21,618 attacks were unleashed on them, representing up to 99% of the targeting of this group in both periods. The year 2018 accounted for the largest share, followed by 2019, which together accounted for about 90% of the targeting of demonstrators in the second period.

* Comparing Targets in the Two Periods

5. When comparing the type of targets within each of the two periods, and by examining the following two figures, it becomes clear that there is a change in the type of targets that Israel focused on in the second period. Some types of targets disappeared while others appeared, and some decreased to a large extent or increased dramatically, which confirms the conclusion of this study, namely that the Israeli occupation forces have changed their military behavior towards GS, in terms of quantity and quality.

* The Proportion of Each Category Within the First Period

* The Proportion of Each Category Within the Second Period

While the most targeted groups in the first period were homes and structures, this changed completely in the second period to become demonstrators, who were the least targeted group in the first period, and the most targeted group in the second period.

Conclusion

1. Discussion Before Analyzing the Results

Despite the importance of Palestine’s accession to the ICC, as an important and influential factor impacting the magnitude and nature of Israeli attacks against GS, the author agrees with the view that Israeli military behavior is affected by several factors and not just one. These would affect to one degree or another in increasing or decreasing the attacks, or restricting or pushing for a decline in the size and nature of those attacks.

Through monitoring and analysis, it is possible to identify four main factors that contribute to one degree or another to the size and quality of Israeli attacks. These factors have sustained effects rather than temporary ones, and they do not include the emergency operational conditions. These types are:

1. Israeli domestic factors.

2. Palestinian factors.

3. Regional factors.

4. International factors.

Under each category, there are a number of influencing factors. If we examine their influence on the attacks, some of them increase them and others reduce. The most important question is: Which of these factors changed in the second period? What caused the quantitative and qualitative decline in Israeli assaults?

It is not possible to analyse all these factors separately. But in general, most of these factors are conducive for more aggression against GS. Among the Israeli domestic factors, for example, is the nature of the Israeli coalition government, the background of the defense minister and the successive elections. Among the Palestinian factors is the state of Palestinian schism, and among the regional and international factors are the counterrevolutions against the Arab Spring uprisings, and the increased US support for Israel respectively. All the mentioned factors encourage further Israeli assaults. Other factors in these two periods also remained the same, such as impact of the international organizations.

However, there are factors that would decrease Israeli attacks, such as the increased deterrence of the Palestinian resistance, and the determination of the Israeli leadership to conclude normalization deals with Arab states, which requires reducing tensions with GS and may interact with Palestine’s accession to the ICC. However, in the author’s view, even if factors interact together to reduce attacks on GS, Palestine’s accession to the ICC is the most important factor. Indeed, the changes and adaptations of Israeli military tactics at the behest of the Israeli leadership match the conditions and clauses of war crimes defined and adopted by the ICC. They are not mere quantitative changes, despite the implications of the latter. Below are some changes the author believes are part of the adaptation:

1. The large decrease in the number of attacks using heavy weapons (96% to 4%) was accompanied with a qualitative change in favor of light weapons. Of every 100 attack in the first period, 87 used heavy weapons, in contrast to 16 out of 100 attacks in the second period. This may be a decision by Israel to adapt to Article 8/2/A/4 of the Rome Statute establishing the ICC which criminalizes “Extensive destruction and appropriation of property, not justified by military necessity and carried out unlawfully and wantonly”, and Article 8/2/B/20, which prohibits “Employing weapons, projectiles and material and methods of warfare which are of a nature to cause superfluous injury or unnecessary suffering”.

2. Israeli forces stopped targeting civilian cars and motorcycles. The number of such attacks dropped from 1,311 in the first period to only 4 in the second. Similarly, the targeting of houses and civilian structures dropped in the second period to represent only 1% of the number of such attacks seen in the first period. This may reflect an Israeli adjustment with Article 8/2/B/5, which prohibits “Attacking or bombarding, by whatever means, towns, villages, dwellings or buildings which are undefended and which are not military objectives;” and Article 8/2/B/24, which prohibits “Intentionally directing attacks against buildings, material, medical units and transport.”

3. The qualitative decrease in the number of women and children killed in relation to the total number of fatalities, representing 21.6 % of the total in the second period compared to 34.4 % in the first. This is while noting that these two categories (women and children) are among the most protected under international law and human rights agreements, which Israel has ratified.

On the other hand, some might say that the first period witnessed two wars contrary to the second period, which may have caused the high number of casualties in this period. Before addressing this, we must clarify that the term “war” used in this paper is a metaphor reflecting what is familiar usage, but the truth is that under international law GS and the West Bank have been in a continuous state of war since 5/6/1967 to date. The more correct term for the hostilities occurring in 2008, 2012, and 2014 is “full military attack.” Moreover, the fact that two such attacks occurred in the first study period but not in the second reinforces the conclusions of this study, namely that Israel launched more full military as well as limited attacks in the first period, while limiting itself mostly to limited attacks in the second period, while noting that all these attacks are considered assault under international law.

2. Results

It may be concluded beyond any doubt from the figures cited above that Israel has altered the scale and nature of its assaults on GS, according to the data of the two study periods. The data has shown conclusively that the period 2015–2019 saw a big decline in the number of Palestinian fatalities, and the number of women and children killed. The number of Israeli military attacks on GS also decreased generally, especially attacks using heavy weaponry such as air strikes and artillery strikes. The number of targets bombed by Israeli forces also decreased, especially homes and civilian structures, while the targeting of civilian vehicles largely stopped.

Therefore, we may conclude that there is a strong indication of fundamental changes in Israeli military tactics in GS following Palestine’s accession to the ICC, while acknowledging that the latter is not the only factor influencing this trend. Nevertheless, it remains the most important factor in the view of the author, evidenced by the qualitative adaptation seen in the statistics above, with the assaults changing both in nature and quantity.

Endnotes

[*] A Palestinian researcher specialized in law and human rights, who holds a doctorate in international law and human rights. Since 2016, he is the head of the legal unit of Al-Quds Forum for Political and Legal Relations (Kudsider) in Istanbul. Former Director General of the Minister’s Office at the Palestinian Ministry of Foreign Affairs. Dahshan has published a number of refereed studies and books.

[1] The term “women” here refers to females over 18 years of age without regard to marital status.

[2] The term “children” here refers to every person who has not completed 18 years of age, of both sexes, according to the definition of the 1989 Convention on the Rights of the Child.

[3] The term “Others” means the rest of the victims, who are not women and children, and include civilians of other groups and ages, in addition to resistance fighters.

[4] The Palestinian Centre for Human Rights, Annual Report 2010, 9/5/2011, p. 18, http://www.pchrGS.org/files/annual/arabic/Annual%202010.pdf (in Arabic)

[5] Al-Mezan Center for Human Rights, A Field Report that Monitors and Documents Human Rights Violations by the Israeli Occupation Forces During the Period from January 1, 2011 to December 31, 2011, 31/1/2012, pp. 3–8. (in Arabic)

[6] Al-Mezan Center for Human Rights, Report on the Israeli Occupation Forces’ Violations of the Rules of International Humanitarian Law in their Treatment of Civilians in Gaza Strip During 2012, 27/2/2013, p. 6, http://www.mezan.org/post/16454 (in Arabic)

[7] Al-Mezan Center for Human Rights, From the Field: Report on the Israeli Occupation Forces’ Violations of the Rules of International Humanitarian Law in Gaza Strip During 2013, 16/2/2014, p. 6, http://www.mezan.org/post/18366 (in Arabic)

[8] The Palestinian Centre for Human Rights, Annual Report Summary 2014, 3/6/2015, pp. 2–6, http://www.pchrGS.org/files/2015/anuual_%20summary_2014.pdf (in Arabic)

[9] Al-Mezan Center for Human Rights, Report on the Israeli Occupation Forces’ Violations of the Rules of International Humanitarian Law and International Human Rights Law in Gaza Strip During 2015, 18/1/2016, p. 3. (in Arabic)

[10] Al-Mezan Center for Human Rights, Violations by the Israeli Occupation Forces of the Rules of Human Rights and International Humanitarian Law in Gaza Strip During 2016, 10/1/2017, p. 3, http://www.mezan.org/post/23199 (in Arabic)

[11] Al-Mezan Center for Human Rights, Violations by the Israeli Occupation Forces of the Rules of Human Rights and International Humanitarian Law in Gaza Strip During 2017, 11/1/2018, pp. 4–18, http://www.mezan.org/post/24927 (in Arabic)

[12] Al-Mezan Center for Human Rights, From the Field: A Statistical Report on the Israeli Occupation Forces’ Violations of the Rules of International Humanitarian Law and Human Rights Principles in Gaza Strip During 2018, 5/2/2019, pp. 3–14, http://mezan.org/post /28077 (in Arabic)

[13] Al-Mezan Center for Human Rights, From the Field: A Statistical Report on the Israeli Occupation Forces’ Violations of the Rules of International Humanitarian Law and Human Rights Principles During 2019, 27/1/2020, p. 3, http://www.mezan.org/uploads/files/158010934487.pdf (in Arabic)

[14] These are the weekly peaceful marches that began on the anniversary of Land Day on 30/3/2018, when Palestinian youths staged a series of protests in Gaza Strip (GS), near the border between the GS and Israel, demanding that Palestinian refugees and their descendants be allowed to return to the land from which they were displaced, as well as protesting the blockade imposed on GS. The protests intensified due to the transfer of the United States Embassy in Israel from Tel Aviv to Jerusalem.

[15] The term “fatalities” or “killed” was adopted according to United Nations reports and reports by human rights organizations, while the term known to Palestinians is “martyrs.”.

[16] Attacks/Strikes may still refer to one attack involving several rockets or projectiles.

[17] Al-Mezan Center for Human Rights, From the Field: A Field Report on Israeli Human Rights Violations, Covering the Period from January 1, 2010 to June 30, 2010, 1/7/2010, http://www.mezan.org/post/10698 (in Arabic); and see the monthly and quarterly reports on the Al-Mezan Center for Human Rights website, under the heading “From the Field.”

[18] Al-Mezan Center for Human Rights, A Field Report that Monitors and Documents Human Rights Violations by the Israeli Occupation Forces During the Period from January 1, 2011 to December 31, 2011, 31/1/2012. (in Arabic)

[19] Al-Mezan Center for Human Rights, A Comprehensive Statistical Report Documenting: The Death Toll and Material Losses that Occurred to Civilians and Their Property in Gaza Strip During the Israeli Aggression “Pillar of Cloud” from 14 to 21 November 2012, 11/11/2013, http://www.mezan.org/post/16480 (Accessed 22/2/2019) (in Arabic); See also Al-Mezan Center for Human Rights, Report on the Israeli Occupation Forces’ Violations of the Rules of International Humanitarian Law in their Treatment of Civilians in Gaza Strip During 2012, 27/2/2013. (in Arabic)

[20] Al-Mezan Center for Human Rights, From the Field: Report on the Israeli Occupation Forces’ Violations of the Rules of International Humanitarian Law in Gaza Strip During 2013, 16/2/2014, pp. 6–35. (in Arabic)

[21] The Palestinian Centre for Human Rights, Annual Report Summary 2014, 3/6/2015; Al-Mezan Center for Human Rights, From the Field: Report on the Israeli Occupation Forces’ Violations of the Rules of International Humanitarian Law in Gaza Strip During the First Half of 2014, 4/7/2014, http://www.mezan.org/post/20167 (in Arabic); Al-Mezan Center for Human Rights, Al-Haq, Al-Dameer Association for Human Rights and the Palestinian Centre for Human Rights, Aggression in Figures: A Report Documenting the Death Toll and Material Losses Suffered by Civilians and Their Property During the Period from 7 July to 26 August 2014 at the Hands of or in the Face of the Israeli Occupation Forces, 2015, http://www.mezan.org/uploads/files/1448259764820.pdf (accessed on 22/2/2019) (in Arabic)

[22] Al-Mezan Center for Human Rights, Report on the Israeli Occupation Forces’ Violations of the Rules of International Humanitarian Law and International Human Rights Law in Gaza Strip During 2015, 18/1/2016. (in Arabic)

[23] Al-Mezan Center for Human Rights, Violations by the Israeli Occupation Forces of the Rules of Human Rights and International Humanitarian Law in Gaza Strip During 2016, 10/1/2017; Al-Mezan Center for Human Rights, the 2016 Annual Report on Violations by the Israeli Occupation Forces Against Fishermen, http://www.mezan.org/post/23222 (in Arabic); and the Palestinians in the Restricted Access Zone in the Sea Off Gaza Strip, 5/1/2017(in Arabic); see The Palestinian Centre for Human Rights, Annual Report 2016, 10/4/2017, https://www.pchrGS.org/ar/?p=13298 (in Arabic)

[24] Al-Mezan Center for Human Rights, Violations by the Israeli Occupation Forces of the Rules of Human Rights and International Humanitarian Law in Gaza Strip During 2017, 11/1/2018 (in Arabic); See also The Palestinian Centre for Human Rights, Annual Report 2017, 4/4/2018, https://www.pchrGS.org/ar/?p=15170 (in Arabic)

[25] Al-Mezan Center for Human Rights, From the Field: A Statistical Report on the Israeli Occupation Forces’ Violations of the Rules of International Humanitarian Law and Human Rights Principles in Gaza Strip During 2018, 5/2/2019 (in Arabic); See also The Weekly Reports for 2018 from the site of the Palestinian Centre for Human Rights, https://pchrGS.org/en/?cat=47 (accessed on 22/2/2019) (in Arabic). It should be noted here that only the report of the Al-Mezan Center was available to the author for this year, but it did not contain all the required data according to the author’s division of the study, so the author referred to the weekly reports of the Palestinian Centre for Human Rights, throughout the whole year, and sorted and classified all events in two tables for 2018, which took a lot of time and effort, but it was worth it, as the data became more accurate and reliable.

[26] Al-Mezan Center for Human Rights, From the Field: A Statistical Report on the Israeli Occupation Forces’ Violations of the Rules of International Humanitarian Law and Human Rights Principles During 2019, 27/1/2020, pp. 3–20. (in Arabic)

[27] Al-Mezan Center for Human Rights, From the Field: A Field Report on Israeli Human Rights Violations, Covering the Period from January 1, 2010 to June 30, 2010, 1/7/2010. (in Arabic)

[28] Al-Mezan Center for Human Rights, A Field Report that Monitors and Documents Human Rights Violations by the Israeli Occupation Forces During the Period from January 1, 2011 to December 31, 2011, 31/1/2012. (in Arabic)

[29] Weekly Reports on Israeli Violations in the Occupied Palestinian Territory on the site of the Palestinian Centre for Human Rights, https://pchrGS.org/ar/?cat=47 (accessed on 22/2/2019) (in Arabic); Al-Mezan Center for Human Rights, A Comprehensive Statistical Report Documenting: The Death Toll and Material Losses that Occurred to Civilians and Their Property in Gaza Strip During the Israeli Aggression “Pillar of Cloud” from 14 to 21 November 2012, 11/11/2013 (in Arabic); Al-Mezan Center for Human Rights, Report on the Israeli Occupation Forces’ Violations of the Rules of International Humanitarian Law in their Treatment of Civilians in Gaza Strip During 2012, 27/2/2013. (in Arabic)

[30] Al-Mezan Center for Human Rights, From the Field: Report on the Israeli Occupation Forces’ Violations of the Rules of International Humanitarian Law in Gaza Strip During 2013, 16/2/2014, pp. 3–35.(in Arabic)

[31] The Palestinian Centre for Human Rights, Annual Report Summary 2014, 3/6/2015 (in Arabic); Al-Mezan Center for Human Rights, From the Field: Report on the Israeli Occupation Forces’ Violations of the Rules of International Humanitarian Law in Gaza Strip During the First Half of 2014, 4/7/2014 (in Arabic); Al-Mezan Center for Human Rights, Al-Haq, Al-Dameer Association for Human Rights and the Palestinian Centre for Human Rights, Aggression in Figures: A Report Documenting the Death Toll and Material Losses Suffered by Civilians and Their Property During the Period from 7 July to 26 August 2014 at the Hands of or in the Face of the Israeli Occupation Forces, 2015. See also The Palestinian Centre for Human Rights, The Annual Report During 2014 on the Violations of the Occupation Forces Against Palestinian Fishermen in GS, 11/1/2015, p. 12, http://www.mezan.org/uploads/files/1430653468922.pdf (Accessed on 22/2/2019) (in Arabic)

[32] Al-Mezan Center for Human Rights, Report on the Israeli Occupation Forces’ Violations of the Rules of International Humanitarian Law and International Human Rights Law in Gaza Strip During 2015, 18/1/2016. (in Arabic)

[33] Al-Mezan Center for Human Rights, Violations by the Israeli Occupation Forces of the Rules of Human Rights and International Humanitarian Law in Gaza Strip During 2016, 10/1/2017 (in Arabic); and the Palestinian Centre for Human Rights, Annual Report 2016, 10/4/2017. (in Arabic)

[34] Al-Mezan Center for Human Rights, Violations by the Israeli Occupation Forces of the Rules of Human Rights and International Humanitarian Law in Gaza Strip During 2017, 11/1/2018 (in Arabic); See also: Palestinian Centre for Human Rights, Annual Report 2017, 4/4/2018. (in Arabic)

[35] Al-Mezan Center for Human Rights, From the Field: A Statistical Report on the Israeli Occupation Forces’ Violations of the Rules of International Humanitarian Law and Human Rights Principles in Gaza Strip During 2018, 5/2/2019, pp. 8–10 (in Arabic); See also The Weekly Reports for 2018 on the site of the Palestinian Centre for Human Rights website, https://pchrGS.org/en/?cat=47 (accessed on 22/2/2019). (in Arabic)

[36] Al-Mezan Center for Human Rights, From the Field: A Statistical Report on the Israeli Occupation Forces’ Violations of the Rules of International Humanitarian Law and Human Rights Principles During 2019, 27/1/2020, pp. 3–20; See also Weekly Reports for 2019 on the site of the Palestinian Centre for Human Rights, https://pchrGS.org/ar/?cat=47 (in Arabic)

June 10th, 2021|Categories: Uncategorized|0 Comments

| Click here to download: >> Academic Paper: Comparative Study on Israeli Attacks on Gaza Strip Before and After Palestine’s Accession to the International Criminal Court … Dr. Sa‘id al-Dahshan |

Al-Zaytouna Centre for Studies and Consultations, 10/6/2021

The opinions expressed in all the publications and studies are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of al-Zaytouna Centre.

Read More:

Leave A Comment