By: Prof. Dr. Walid ‘Abd al-Hay.[1]

(Exclusively for al-Zaytouna Centre).

Introduction:

Since Daniel Kaufmann developed in 1996 his model of qualitative measurement of political stability worldwide,[2] the research in this respect has expanded, most importantly developing the main and sub-indicators of measuring the phenomenon, reaching about 350 indicators, and measurement methods and main measured dimensions, which appeared in three approaches to measuring political instability, namely: [3]

1. The propensity for regime or government change.

2. Political upheaval or violence in a society.

3. Frequent change and instability in the “strategic policies and plans” of the state.

Based on the above, we will determine the level of political stability in Israel throughout 2000–2020, and sometimes we will refer to some indicators until 2021 and 2022 depending on available data. Then, we will determine the mega-trend of the phenomenon comparing it with the levels of stability of various countries and, consequently, we’ll determine Israel’s worldwide rank of political stability.

The measurement model is based on a scale ranging between +2.5 (the highest degree of stability) and –2.5 (the lowest degree of stability) where, based on time series analysis, we will determine the level of political stability in Israel in 2030.

| Click here to download: >>Academic Paper: The Future of Political Stability in Israel in 2030 … Prof. Dr. Walid ‘Abd al-Hay |

Measuring Indicators of Political Instability in Israel [4]

In this study, we will rely on theGlobalEconomy.com model,[5] taking advantage of some aspects Kaufman highlighted, and we will focus on presenting the 12 main indicators of political stability, each of which is divided into a varying number of sub-indicators according to the nature of the main indicator.

When applying these main indicators to Israel, we find the following:

1. Government stability: Throughout 2000–2022, the executive authority was assumed by six prime ministers, but the term of their rule varied greatly as follows:[6]

a. Ehud Barak: One year and 245 days.

b. Ariel Sharon: Five years and 39 days.

c.Ehud Olmert: Two years and 351 days.

d. Benjamin Netanyahu: 15 years and 92 days, of which approximately 12 years were included in the study period.

e. Naftali Bennett: One year and 17 days.

f. Yair Lapid: About two months.

The previous distribution reveals a great discrepancy in the duration of stability in power, sometimes reaching more than 15 times between one government and another while four of the six governments did not complete their four-year term.

2. Socioeconomic conditions: Such as class differences, income level, crime, etc. It is sufficient to consider the Gini index where it shows that fairness of income distribution has improved, but by no more than 1% in about 22 years.[7]

3. Investment profile: In terms of their stability, increase or decline, etc. Financial reports of various international bodies indicate that the volume of foreign investments in the Israeli economy has been increasing since 2008,[8] which contributes to absorbing some social tensions.

4. Internal political conflicts: In the past three years (2019–2022), five parliamentary elections were held due to the cracks in the structure of governments. They were held in April and September 2019, March 2020 and March 2021, and a fifth election is expected to be held in November 2022. This irregular number of general elections reveals the fragility of government coalitions and internal conflict among political forces. It also indicates power rotation at irregular intervals, as we mentioned in the first point. Moreover, throughout the history of Israel, no party has obtained a majority in the Knesset, and this explains why the “average” number of parties participating in the elections has reached about 27 throughout 1977–2022. What adds insult to injury is that many parties appear and disappear within short periods of time as, for example, 40% of the parties that won the 2015 elections did not exist in the 2005 elections. The fundamental differences between parties revolve around two strategic issues, namely, the means of settling the Arab-Zionist conflict, on the one hand, and the identity of the state (secular or religious), on the other hand. In addition, there is the continuous increase in the electoral threshold, which leads to a continuous change in the participating parties, especially the smaller ones. For example, during the first 40 years of the Israeli political system, a party was required to obtain 1% of the votes; then, the percentage was raised to 1.5% in 1992 and to 2% in 2004 while reaching 3.25% since 2014.[9] Also, elections were held 24 times in the history of Israel, and if we divide these times into three sub-stages, we will find that that popular participation in parliamentary elections at each stage is lower than the previous one, which is a negative indicator.[10]

5. External conflicts: Without going into the details of the military conflicts between Israel and the Arab countries since 2000, especially on the Lebanese and Palestinian fronts in Gaza and i Syria, besides the daily clashes and various attacks targeting Palestinian civilians, Israel has the highest number of convictions by the United Nations, a matter that has repercussions on the internal structure and on the image of Israel in international public opinion.[11]

6. Corruption: Corruption is defined as “the abuse of entrusted power for private gain.”[12] Transparency reports indicate that, between 2000 and 2021, the rate of corruption in Israel is almost constant, with a slight tendency to increase. Quantitative indicators have revealed that the corruption has increased in the five years between 2016 and 2021 by about five points. Transparency in Israel scored 64 points in 2016 but decreased to 59 points in 2021.[13]

7. Interference of the military institution in political decisions: Given the priority of security in Israeli policies, the Israeli army is a key partner in strategic decision-making. The Cabinet, a supreme body concerned with security-related decisions, but one which has lost its official character since 1990—not to mention the role taken by the National Security Council (NSC) formed in 1999—still plays a role in decision-making. This causes disagreements with the government, increasing government instability to some extent, and even enhancing the prospects of the continuation of political stability in Israel, as will become clear next.[14]

8. Religious tensions: In addition to the tensions between Arabs (Muslims and Christians), on the one hand, and Israelis and the religious Jews, on the other hand, the Israeli society has witnessed polarization within Jewish religious movements, and between these movements and secular ones. Their conflicts revolve around many issues, especially democracy and the relationship between the state and religion.[15]

9. Rule of law: The rule of law rests on four pillars: accountability and responsibility for all; justice that means the application of law to everyone, on the same basis and regardless of any considerations; transparency in the application of the law to everyone; and that those implementing it are independent of the influence of any party. The record of Israel shows that this indicator declined clearly and significantly throughout 2000–2009, improved throughout 2010–2015 and deteriorated again from 2015 until now (2022), bringing the level after 2020 to almost the same level in 2000; yet, it remains higher than the world average.[16]

10. Ethnic tensions: Israeli studies tend to divide the Israeli Jewish society into four main ethnicities: Ashkenazim, Sephardic, Russian and Ethiopian (African). These four groups vary in their share of income, political and military influence as well as social status. Often, manifestations of violence take place between these ethnicities.[17]

11. Democratic accountability: It means how far is it possible for political forces, parliamentarians or those who assumed their positions through democratic processes to be held accountable. It is noted that this sub-indicator of political stability decreased by about 13 points throughout 2016–2020, although it witnessed an improvement throughout 2010–2016 reaching 21 points.[18]

12. Government effectiveness: The government effectiveness indicator is calculated based on perceptions related to six dimensions: the level of public services; the level of civil service; the degree of its independence from political pressures; policy formulation; the level of policy implementation; and finally the credibility of the government’s commitment to these policies. Quantitative data of the period 2010–2020 indicate that the 2010–2014 period witnessed a decline in the Government effectiveness of Israel, then an improvement in 2015–2017, followed by deterioration from 2018 until now (2022), with a decline rate of 0.38 points out of 2.5 points (where 2.5 points are considered the strongest in measuring government effectiveness), reaching 1.1 points.[19]

The Overall Indicator of Political Instability in Israel

The model for measuring political stability ranges between -2.5 (the highest degree of instability) and +2.5 (the highest degree of stability). Stability values are determined based on the 12 main indicators mentioned above, and the country’s rank is determined based on the measurement results and comparing them with the rest of the countries. Then, the trend is determined for each country (the increase or decrease in the rate of stability) and compared with the global average.[20]

Table 1: Trends of Political Instability in Israel since 2000

| Year | Political stability index [21] | Israel’s international ranking | Number of countries whose stability was measured | Global rate of instability |

| 2000 | -1.04 | 153 | 185 | -0.01 |

| 2001 | -1.25 | 158 | 185 | -0.05 |

| 2002 | -1.46 | 164 | 185 | -1.01 |

| 2003 | -1.52 | 175 | 192 | -0.03 |

| 2004 | -1.32 | 170 | 193 | -0.05 |

| 2005 | -1.25 | 165 | 193 | -0.05 |

| 2006 | -1.26 | 167 | 194 | -0.05 |

| 2007 | -1.25 | 170 | 194 | -0.05 |

| 2008 | -1.32 | 171 | 194 | -0.05 |

| 2009 | -1.63 | 179 | 194 | -0.07 |

| 2010 | -1.34 | 172 | 194 | -0.07 |

| 2011 | -1.20 | 167 | 194 | -0.06 |

| 2012 | -1.08 | 161 | 194 | -0.06 |

| 2013 | -1,10 | 163 | 194 | -0.06 |

| 2014 | -1.04 | 167 | 194 | -0.05 |

| 2015 | -1.09 | 171 | 194 | -0.06 |

| 2016 | -0.79 | 155 | 194 | -0.05 |

| 2017 | -0.89 | 160 | 194 | -0.05 |

| 2018 | -0.91 | 163 | 194 | -0.06 |

| 2019 | -0.79 | 154 | 194 | -0.07 |

| 2020 | -0.83 | 156 | 194 | -0.07 |

| 2021 | -0.76 | 148 | 179 | -0.08 |

| 2022 | -0.75 | 146 | 179 | -0.09 |

Analysis

Table 1 indicates the following results:

1. By converting the adopted scale into percentages, the rate of instability in Israel ranged between 65.2% in 2009 (the highest throughout 2000–2022) and 41.6% in 2000 and 2014 (which is the lowest rate).

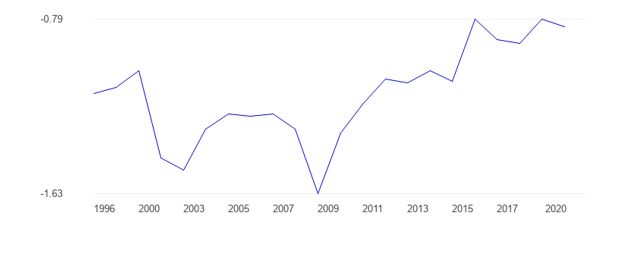

2. The comparison between global instability rate and its rate in Israel reveals that the latter is always higher than the former. This means that the impact of global instability on Israeli one is limited, which reinforces the idea that the internal factors for Israeli political instability, rather than the international environment, are the decisive variables. This means that the correlation coefficient between Israeli instability and international instability is clearly weak. In return, the general trend of global political instability tends to rise slightly, while Israeli instability tends to decline, confirming that the repercussions of international instability do not show their impact on the Israeli side.

3. The Israeli global rank in the level of political stability ranged between 179 (among 194 countries) in 2009, which is the worst, and 146 (among 179 countries), a rank which places Israel among the countries with the worst instability throughout 2000–2022.

4. It is noticed that the stability rate in Israel throughout the measurement period 2000–2022 always falls on the negative side (see table 1 and graph 2).

5. However, it should be noted that the stability ratio has begun to improve (although it remains in the negative level), and although this improvement does not assume a linear trend, the longer historical series analysis indicates an improvement (see graph 2).

6. Based on the foregoing, the political stability in Israel in 2030 will remain in the negative side, but it will be better than that in 2000–2022.

Graph 1: Mega-trend of Israeli Political Stability 1996-2020 [22]

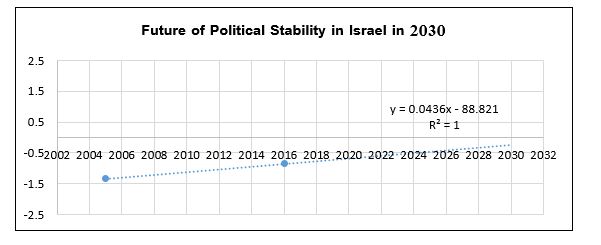

The Future of Political Stability in Israel

The quantitative data of the main and sub-indicators of political stability indicate that Israel will remain in the negative range according to the political stability index. This means that, until 2030, Israel will remain an unstable state due primarily to the local conditions, then the regional and international ones.

Also, the level of instability will decrease throughout 2022–2030, but it will remain, as we mentioned, in the negative side and within the group of unstable countries, and the rate of instability will remain between (–0.3 and –0.4). This will keep Israel in the ranks between 107 and 111 based on the measurement of 192 countries. (see graph 2).

Graph 2: Time Series for Measuring Political Instability in Israel 2000-2022 [23]

Conclusion

It is noted that political instability in Israel has increased in the periods following escalated confrontations between the resistance and the Palestinian people on the one hand, and the Israeli forces and settlers on the other hand. This is evident in the periods after the Intifadahs (uprising) and major confrontations with Gaza Strip, but particularly after the religion-based confrontations (see graph 2).

Based on the above, increasing political instability in Israel is linked to the activities of the resistance, the halt of negotiations and the suspension of security coordination with Israel. Furthermore, this instability increases when the differences between Jewish sub-cultures (Ashkenazim, Sephardi, Russians and African Jews) are instigated, and also between the religious and secular movements. Some Jewish movements may contribute to this instability, such as the Neturei Karta movement or the New Historians.

There is no doubt that the waves of official Arab normalization with Israel will lead to a more favorable environment, enhancing the chances of improving the stability of Israel. They might lead to a transition from being in the current negative level to reaching the beginning of the positive level later, but that depends on three factors:

1. The strategy of the resistance forces to deepen political instability in Israel, the most important of which is the abolition of security coordination with Israel and the dissolution of its apparatuses, and even threatening those who continue to work in these apparatuses. Remarkably, Israeli studies indicate the close relationship between the level of stability in Israel and security coordination.[24]

2. Exacerbation of societal disparities among the Jews of Israel.

3. The reflection of regional and international developments on the political stability in Israel.

According to quantitative measurement, we expect Israel to remain within the area of negative political instability until 2030 unless the low probability-high impact factor intervenes.

[1] An expert in futures studies, a former professor in the Department of Political Science at Yarmouk University in Jordan and a holder of Ph.D. in Political Science from Cairo University. He is also a former member of the Board of Trustees of Al-Zaytoonah University of Jordan, Irbid National University, the National Center for Human Rights, the Board of Grievances and the Supreme Council of Media. He has authored 37 books, most of which are focused on future studies in both theoretical and practical terms, and published 120 research papers in peer-reviewed academic journals.

[2] Daniel Kaufmann et al., The Worldwide Governance Indicators: Methodology and Analytical Issues, site of The World Bank, September 2010, http://info.worldbank.org/governance/wgi/pdf/wgi.pdf

[3] Several international and academic institutions contribute to the development of models for measuring political stability, and there are different approaches to determine the approved indices of political stability (or lack thereof), and methods for determining the weights of each indicator. The model developed by Daniel Kaufman and others, and adopted by the World Bank, can be considered the most famous and referred to, but other institutions contributed to the development of the model bringing the number of indices to measure political stability to about 352 sub-indicators.

See for details: Political Instability, Indices of, International Encyclopedia of the Social Sciences, site of Encyclopedia.com, 5/8/2022, https://www.encyclopedia.com/social-sciences/applied-and-social-sciences-magazines/political-instability-indices

[4] Daniel Kaufmann et al., Governance Matters IV: Governance Indicators for 1996–2004, The World Bank, June 2005, https://openknowledge.worldbank.org/bitstream/handle/10986/8221/wps3630.pdf?sequence=1&isAllowed=y

[5] Political Stability – Country Rankings, site of TheGlobalEconomy.com, https://www.theglobaleconomy.com/rankings/wb_political_stability/

[6] List of prime ministers of Israel, site of Wikipedia, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/List_of_prime_ministers_of_Israel

[7] Israel – GINI index (World Bank estimate), site of indexmundi, https://www.indexmundi.com/facts/israel/indicator/SI.POV.GINI

[8] The Economic Impact of Foreign Investments in Israel, site of Invest in Israel, March 2019, https://investinisrael.gov.il/HowWeHelp/downloads/The%20economic%20impact%20of%20Foreign%20Investments%20in%20Israel.pdf; Israel Foreign Direct Investment, site of Trading Economics, https://tradingeconomics.com/israel/foreign-direct-investment; and Israel: Trade and Investment Statistical Note, site of The Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD), 2017, https://www.oecd.org/investment/ISRAEL-trade-investment-statistical-country-note.pdf

[9] Jewish Studies, The Sheridan Libraries, site of Johns Hopkins University, Fall 2020, https://guides.library.jhu.edu/c.php?g=202541&p=7656917

[10] Turnout of voters for the parliamentary elections in Israel from 1992 to 2021, site of Statista, 9/6/2022, https://www.statista.com/statistics/990777/israel-parliamentary-voter-turnout

[11] UN condemned Israel 17 times in 2020, versus 6 times for rest of world combined, site of The Times of Israel, 23/12/2020, https://www.timesofisrael.com/un-condemned-israel-17-times-in-2020-versus-6-times-for-rest-of-world-combined/

[12] Corruption Perceptions Index, site of Transparency International, https://www.transparency.org/en/cpi/2021

[13] Israel Corruption Index, Trading Economics, https://tradingeconomics.com/israel/corruption-index

[14] Amnon Sofrin, The Two-Group Decision Model: Applications to Military Intervention in Middle East, site of Reichman University, 22/2/2017, https://www.runi.ac.il/media/o2gjbrmg/the-two-group-decision-model-applications-to-military-intervention-in-the-middle-east.pdf

See about the weaknesses of the decision-making process in Israel and the consequences thereof, especially due to the role of the military institution:

Charles D. Freilich, “National Security Decision-Making in Israel: Processes, Pathologies, and Strengths,” The Middle East Journal, vol.60, no.4, Autumn 2006, pp. 643–660.

The impact of this on political stability is evident in the widening gap between the military and the civilian segment in the Israeli political forces, and a study issued by a German institute found that the establishment of parties by retired officers is an indication of a deeper crisis in the structure of the political authority that would affect the political decision and government stability. See details in: Yoram Peri, The Widening Military–political Gap in Israel, site of Stiftung Wissenschaft und Politik, 20/1/2020, https://www.swp-berlin.org/10.18449/2020C02/

[15] Gideon Aran and Ron E. Hassner, “Religious Violence in Judaism; Past and Present,” Terrorism and Political Violence Journal, vol.25, no.3, 2013, pp. 365–390.

[16] Israel: Rule of Law, TheGlobalEconomy.com, https://www.theglobaleconomy.com/Israel/wb_ruleoflaw/

[17] Noah Lewin-Epstein & Yinon Cohen, “Ethnic origin and identity in the Jewish population of Israel,” Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies, vol.45, no.11, 2019, pp. 2134–2136.

See also the details of violence between these ethnicities in: Walid ‘Abd al-Hay, The Correlation between Social Deviance and Political Violence in Settler Colonial Societies: Israel as a Model, site of Al-Zaytouna Centre for Studies and Consultations, 10/12/2020, https://eng.alzaytouna.net/2020/12/10/academic-paper-the-correlation-between-social-deviance-and-political-violence-in-settler-colonial-societies-israel-as-a-model/#.YwuXcNNBxPY

[18] Voice and Accountability – Country Rankings, TheGlobalEconomy.com, https://www.theglobaleconomy.com/rankings/wb_voice_accountability/

[19] Government Effectiveness – Country Rankings, TheGlobalEconomy.com, https://www.theglobaleconomy.com/rankings/wb_government_effectiveness/

[20] Political Stability – Country Rankings, TheGlobalEconomy.com.

[21] A number of measurement models have been relied upon especially The GlobalEconomy.com, see: Political Stability – Country Rankings, TheGlobalEconomy.com.

See also: What Methodology was Used For the Ratings?, site of Fragile States Index, https://web.archive.org/web/20170904072810/http://fundforpeace.org/fsi/frequently-asked-questions/what-methodology-was-used-for-the-ratings/; Country Dashboard, Fragile State Index, https://fragilestatesindex.org/country-data/; and Israel: Political Stability, TheGlobalEconomy.com, https://www.theglobaleconomy.com/Israel/wb_political_stability/

[22] Israel: Political Stability, TheGlobalEconomy.com.

[23] Future results are reached using the time series method, where the whole period is divided into two equal periods. Then the average is taken for each period, and a graph is made on which the median values in the two groups are placed, so that the average value of the first group is against the “middle year of the group” on the x-axis, and the same is the case with the second group. Then, the two points of the two groups are joined together, and the line is extended to be opposite the future year in which the phenomenon is to be measured. The value of the future year is the value parallel to the point at the opposite end of the line on the y-axis.

[24] Ali Al-Awar and Yohanan Tzoreff, The Rift in Fatah Which Threaten Security Stability, is a Challenge – and Not Only for Israel, site of Institute for National Security Studies (INSS), 15/8/2022, https://www.inss.org.il/publication/fatah/

| Click here to download: >>Academic Paper: The Future of Political Stability in Israel in 2030 … Prof. Dr. Walid ‘Abd al-Hay |

Leave A Comment